Earth: Istražite Prirodna Čuda planete Zemlje kroz Društvenu Igru

U svijetu društvenih igara, Earth se ističe kao igra koja kombinira ekološku svjesnost, strategiju i prekrasnu umjetnost. Ako ste ljubitelj

Time to wrap my coverage of BGG.Spring, an event that ended, gosh, ten days ago so that I can move on to other things…such as wrapping my coverage of GAMA Expo 2023, which took place in April, or perhaps wrapping my coverage of the trick-taking event that I attended in January 2023.

Game announcements are so plentiful that I find it hard to focus on what I’ve seen and played before new games fill my every view — although sometimes the two experiences, the new game and me playing something, coincide, as with…

• Lacuna is a two-player game from designer Mark Gerrits and publisher CMYK that will be released on July 6, 2023, with a pre-order being available from the publisher, and it falls into the rare category of a perfect information, two-player abstract strategy game that could find itself a mainstream success, depending on marketing and availability, of course — but I’m getting ahead of myself.

To set up the game, lay out the cloth mat, then sprinkle the 49 wooden tokens — seven each in seven colors — from the storage tube onto the mat like salt on mashed potatoes. (The tube has a plastic top with a small opening to ensure that the tokens don’t come out all at once.)

Your goal in Lacuna is to win four colors; to win a color, you need to collect at least four tokens of that color. The first player collects a wooden token of their choice from the mat, then takes the first turn. On a turn, place of your metal pawns anywhere on the line between two tokens of the same color, then collect those two tokens. This line must be unobstructed by other tokens or player pawns.

Ken Shoda uses the included ruler to check for legal placement

Players keep taking turns until they’ve placed all six of their pawns. At that point the first player has collected 13 tokens and the second player 12, so no one could have won the game, although someone might have won a color or two.

For each remaining token on the board, you award it to the player whose pawn is closest to it. Here’s an overhead view of a game at that point:

For the most part, you can easily tell who has claimed which tokens. The light blue in the upper left goes to the gold player, for example, while the light blue at the far left goes to silver. When you’re not sure, use the included ruler to determine which pawn is closest to a token. After all the tokens have been claimed, one of the players will have won four colors and therefore won the game.

Lacuna is beautifully simple in its design, and the publisher has matched that beauty in its presentation of the game. The cloth mat, the heavy metal pawns, the wooden tokens with their unique shapes and patterns, the salt shaker storage container — all of it is satisfying to hold, touch, and use, and that satisfaction helps mask the difficulty of playing well, which is why I think people who don’t normally enjoy perfect information, abstract strategy games would still find it pleasing to play.

Every turn is two-fold. When you place a pawn, you claim two tokens, which helps move you toward victory, and you call dibs on other tokens around you, but those tokens can be snatched away by an opponent’s placement. When you look at the image below, you’ll see all sorts of possibilities for what you can claim now, but what might you get later?

One rules clarification: If you place a pawn between two pairs of tokens simultaneously, you claim only one pair, so you can’t place between two purple and two deep blue on the left and claim both pairs at once — but you can place at that intersection anyway, claim one of the pairs, and block the opponent from claiming the other pair.

That said, this layout has a rich cluster of blue and purple, so you can’t block everything. In fact, silver pretty much has a lock on a blue token on the right, so silver might want to place on the line between the two blue on the left because then they’re pretty much locking in the blue on the far left, which will win them blue.

Placing on the larger spot possibly blocks anyone from linking that far left blue to other blues

However, they’ve then used two pawns to win one color, which is probably not a winning strategy. What else are those two pawns going to be able to claim? Will they participate in other ways? That’s not clear because both of you have more pawns to place — and the image two above shows that those dark blue tokens have been claimed before the final distribution.

The gameplay is beautifully clear, and you’re pulled in multiple directions thanks to the web of possibilities. The clearest conflict: Should you use two pawns to claim four tokens of the same color and remove all doubt of who won it, or do you use only one pawn, claim two, and somehow fence off two more beyond a doubt? Is that a sure thing? Not necessarily because as tokens are removed, other tokens become targets when previously they were blocked from being claimed.

I’ve played Lacuna three times, twice on a review copy and once with James Nathan, who is a scout for CMYK and who was playing the game at BGG.CON 2022, and I’m entranced. Intriguingly, the victory condition — four or more tokens of four or more colors — is also a victory condition in Tintas, a wonderful game that I covered in 2016, but Tintas bears the traditional austere look of an abstract strategy game while Lacuna looks lighter and more joyous…despite requiring exactly as much thought as Tintas!

• Another new game (at least in English) that hit the table was Inside Job from Tanner Simmons and KOSMOS.

In this 3-5 player trick-taking game, each player gets a secret role card, with all but one player being an agent and that one player being the insider, who is trying to thwart the agents from completing missions. Each player gets a hand of cards from a standard 52-card deck.

At the beginning of a trick, the starting player looks at two mission cards, discards one face down, then reveals the other. Each mission shows a trump color for that trick along with a task to be completed, e.g., all cards played must be between 7 and 13, or the second card played must win the trick. The starting player leads a card from their hand that other players must follow, if possible — except for the insider, who can play what they like. If the mission succeeds because players did what was written on the card, then you place the mission in a “success” pile; otherwise, discard it. Whoever played the highest card wins an “intel token”, which looks like a briefcase, then starts the next round by drawing two mission cards.

If the agents succeed at a certain number of missions, which varies by player count, they win immediately, and if the insider ever collects enough intel tokens, they win immediately — and if both happen simultaneously, the insider wins. If neither side wins by the final trick, everyone votes for who they think the insider is, winning only if the insider has more fingers pointing at them than anyone else has.

We played twice…but not really since some of the rules were not taught:

— We just flipped missions from the top of the deck, so the starting player had no say in the course of the round beyond their choice of lead card.

— We talked about our cards in hand, saying things like “Don’t lead green”, when you’re not supposed to talk about cards in hand, only cards already played.

— We didn’t wager intel tokens, a move in which you can place a previously won intel token on a played card to make it part of the trump suit; whoever wins this trick collects all wagered intel tokens, in addition to winning one for the trick itself.

So I don’t know what to think at this point. I hope to play again, worrying a bit that the initial mission choice might take longer than I like, but it can’t possibly slow the game down as much as the between trick activity in American Psycho: A Killer Game.

• The Number is from Hisashi Hayashi and Repos Production, this being a licensed version of Hayashi’s self-published Suzie-Q.

Each turn, each player secretly writes a three-digit number on their board, then they reveal their boards and arrange them from low to high. If any digit in the highest number is included in a lower number, that player’s board is removed and they score 0 points for this turn. Keep evaluating boards until you have a highest board with no digits repeated by others. Each player still in the round scores points equal to the value of the first digit in their number, and the player with the highest number receives a bonus — then they cross out all the digits in their number on their scoring board and can’t use these digits again for the rest of the round.

After five turns, with everyone doubling the value of their winning highest digit in the fifth turn, you tally your points — which includes 1 point for each crossed-off digit — then start a new round with all digits being available for everyone. After two rounds of five turns, whoever has the highest combined score wins.

I forgot to take a picture during play…

The Number is weird in that you have an obvious opening move of 999. If no one else writes a 9, you score 9 points and the round bonus, then only one digit is off limits for you in the remainder of the round. If someone else writes a 9 in their number, they bump you out, but now they likely can’t use 9 again while you still can…so will anyone else write a 9 since it prevents them from writing 999 at some point?

Thus, you’re all guessing who might write what when, with the open knowledge of which digits people can’t write. If two people write the same number, they score or are eliminated together…but if we both have 9s open late in the round, I might write 799 in the hope of eliminating you and being the high number, and you might in turn write 777 to take me out. I need more plays to even know what I think about this game…

• My co-worker Candice Harris was eager to play more Dual Gauge from Amabel Holland of Hollandspiele and set up the Honshu side of the Dual Gauge: Honshu & Wisconsin Maps expansion.

Dual Gauge is somewhat 18xx-light, with players initially holding an auction for a share in each rail company in the game, then playing in alternating operating rounds and stock rounds until the game ends, something that triggers due to running out of trains, track, spaces for stations on the map, shares available for purchase, or other things specific to a map.

After one operating round

The title refers to the dual types of track available for purchase: narrow and standard. Narrow track is cheaper to build, but you can run a train on it from only one station to the next, whereas a train on standard track can travel to two stations on a line.

Whoever holds the most shares in a company controls the actions of that company: laying track, placing stations, buying trains, running routes, then either paying out the earnings for that round or withholding that money in the company’s treasury. Your long-term goal is to end up with the most money, which is earned by (1) owning shares in companies that increase in value and (2) collecting payouts.

At game’s end

It was the first play for at least two of the four of us, so possibly we played stupidly, but in the middle of the game it felt like many of us were spinning our wheels, running the same routes each turn and not advancing our company’s network in meaningful ways. If you don’t build track, then the company must withhold money earned on routes and its stock price falls based on the number of shares issued or converted into stations, so we often built track to nowhere because we couldn’t see what to do productively. I suppose at times you want to tank a company’s share price, but we couldn’t see why.

Bottom line: Dual Gauge seems like the type of game where playing once is akin to not playing at all. Only at game’s end can you assess where and when people made smart choices and whether you should have made other moves, then you apply all of that info to your next playing. If you don’t play again, then you’re left only with the feeling that you played horribly.

• While at the flea market, I convinced my friend Ken Shoda to buy SHŌBU, a 2019 release from designers Jamie Sajdak and Manolis Vranas and publisher Smirk & Laughter Games. Ken loves abstract strategy games and seemed unconvinced by the look of the game, but caved and bought it.

Here’s the starting position:

Image: Doctor Meeple

A turn consists of two steps: passive, then active. First, move a stone of your color on one of the boards close to you. Move in a straight line orthogonally or diagonally as far as you want, stopping at the edge of the board or another piece.

Second, move a stone of your color on either board of the color opposite of which you first moved on, duplicating the move you made initially, e.g., if you moved forward two spaces on the dark board, you must move forward two spaces on either light board. In this action, you can push one stone of the opponent’s, ideally pushing them off the board. If you can’t make this active move, then go back and make a different passive move.

If you push all of the opponent’s stones from one board, you win.

Ken and I played twice, with the starting player winning both times, which made Ken worry about a starting player advantage, then we played twice more, with each of us starting one of the games, and I beat Ken both times. Theory — rejected!

SHŌBU sort of feels like four games in one thanks to the multiple boards, but everything is linked in complicated ways. In the image above, the white stone on the upper left board is pretty much useless. As a passive move, Ken can move it toward him 1-3 spaces or diagonally or horizontally one space, with none of those moves allowing the white stone in the lower right — a stone I am about to push off the board for the win — to move to safety.

But to give that stone on the dark board more freedom of movement, Ken would have to first move a stone on the light board close to him, and his options there are also limited.

How we got to that position took a long time, and it’s hard to reconstruct exactly how things went wrong. In a way, you can think of the boards closest to you as programming boards. You want to keep your options on those boards as open as possible, which is why the opponent wants to attack you there — except that sometimes removing a stone is a good thing since it gives you more room in which to move.

In any case, I made a good call, and Ken will take it back to Japan to introduce it to others at his abstract game club.

• While in Dallas for BGG.Spring, I got to visit Common Ground Games, which has an impressive selection of new games for sale, not to mention dice and other geeky stuff, along with tables for events.

Common Ground Games has a giant preschool-style stack of Frosthaven by the front door, perhaps as a lure for thieves who think that they can grab a copy and scoot out the door as they will instead be dragged to the floor by its weight, their fingers pinned under the box, giving the employees plenty of time to call the police.

It also has a $250 giant squishable frog that I passed on buying with regret, not because I want a giant squishable frog, but because I robbed my wife of the joy of telling everyone in her family that I spent $250 on a giant squishable frog. She would have liked that.

Every so often I do something completely out of character, sometimes without really knowing why and sometimes intentionally. Whenever she learns of such things and acts shocked, I get to say, “You don’t know the real me!” Married life…

The BGG media team also visited Velvet Taco, where I stared hypnotically at a painting of Marie Antoinette. Seriously, I couldn’t not look at this painting. (Here’s more work from artist Laura Shull.)

• I’ll close with words of thanks to Ken Shoda. To start, Ken offered to pick up games for me at Tokyo Game Market in late 2019 that I would pay him for the next time I saw him, probably at Game Market the following May.

Whoops.

But Ken held on to those games, then held on to even more games when he was clearing out stock of various nestorgames titles in April 2021 when Game Market first re-opened.

Ken stuffed all of those games in his bag and delivered them to me at BGG.Spring, where I met him with a big stack of bills.

Beyond that, Ken’s taste in games line up perfectly with mine: card games of all sorts, perfect information abstract strategy games, and pretty much anything from Reiner Knizia. In short: cards, combinatorics, and Knizia.

We’ve played many games together over the years, and however much I think I know about games, Ken’s knowledge of Knizia titles is encyclopedic. What’s more, he recalls particular games in a way that I often now struggle to do. While looking around the charity flea market, Ken picked up a copy of Reiner Knizia’s game Motto and told me I should get it: “Don’t you remember? We played it several times at a temple on one of your trips to Japan, and you told me you don’t have it.”

The game didn’t look familiar to me, so I looked it up on BGG to find a 5.5 rating on a title from Polish publisher Granna that never made a splash on the market and that likely disappeared on clearance shortly therefter.

And I also found that I had played it three times in May 2016. Then I looked at the pictures on my phone, and there we were, playing Motto at the Sensō-ji Temple in Asakusa, Tokyo.

How could I not buy this game?

Many thanks once again, Ken, for the wonderful time playing games with you at BGG.Spring, and ideally we’ll see one another again at SPIEL ’23!

Ken is also a math guy, like me

U svijetu društvenih igara, Earth se ističe kao igra koja kombinira ekološku svjesnost, strategiju i prekrasnu umjetnost. Ako ste ljubitelj

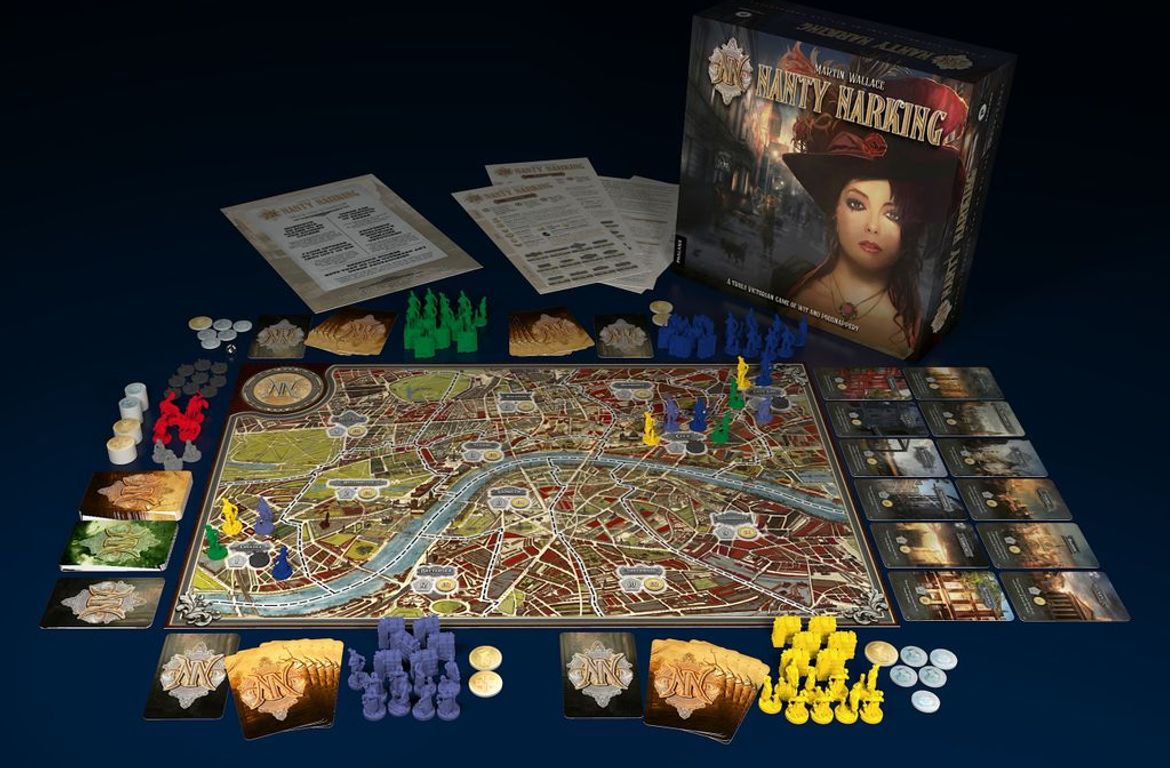

U svijetu društvenih igara, rijetko koja igra uspijeva obuhvatiti bogatstvo povijesti, strategije i priče poput Nanty Narkinga. Ova igra, smještena