Earth: Istražite Prirodna Čuda planete Zemlje kroz Društvenu Igru

U svijetu društvenih igara, Earth se ističe kao igra koja kombinira ekološku svjesnost, strategiju i prekrasnu umjetnost. Ako ste ljubitelj

[Editor’s note: I’m aware of the Nov. 16, 2022 Dicebreaker article regarding accusations of non-payment by and “a toxic environment” at publisher Pandasaurus Games, but Clarence and Ashwin started working on this diary months ago, and I want to give them a chance to tell their story. Please direct any comments about the publisher’s business practices to this thread instead of posting them here. —WEM]

The Wolves has had quite an eventful path to publication. We wanted to invite you to take a closer look at that journey with us as we share how we co-designed a game in the midst of a pandemic.

Lone Wolves No More

Clarence: The Tabletop Mentorship Program is a crown jewel of the tabletop design community. They run a service that matches up volunteer mentors with mentees across all different disciplines within tabletop game design. The program is open to everyone and completely free of charge. They matched me with my own mentor, Rob Newton, who helped me pitch what eventually became my first published design, Merchants of Magick.

Since then, I’ve served as a mentor myself many times, hopefully giving a helping hand to the next generation of designers. One of those times, I was assigned to mentor a passionate gamer who wanted to dive into game design. He had a lot of ideas, but hadn’t made anything tangible yet. I was new myself and had only been designing games seriously for about six months, but if you know things that you didn’t know when you started, then you can be a mentor, so I thought I might be able to help him out. That mentee was Ashwin, my eventual co-designer on The Wolves.

[twitter=1205189064024047617]First time meeting Ashwin at PAX Unplugged 2019

Ashwin: Just being completely transparent here, with no intention of being punny, I felt like a lone wolf prior to all of this. I was/am missing home, missing family, wishing I could build something for myself. A mid-late 30s transplant in Seattle where art, music, dance and innovation at the community level is masked by not only gray skies and awful traffic congestion, but also mass transit on life support and overpriced housing everywhere you go! Struggling to find definitions in my life, I stumbled upon the Seattle Tabletop Game Designers community, a group that I once mistook for a board game meetup, but is now a group that I call family.

After being a joyous fool overly excited about everyone’s projects, one person asked me a simple question, “Ashwin, where’s your game?” I stopped showing my face for a few weeks. I always run away. I always do this. When adversity hits, I hit up my favorite burrito joint, play hours of Dota 2, and drown myself in box wine. This wasn’t even adversity! This was just me not committing to something creative, joyful, and full of meaning that I quickly discovered about myself when I took a leap, a pounce? of faith. After overproducing a few mechanical concepts trying to show off what I found in the aisles of Michaels and Home Depot, I was guided to this Tabletop Mentorship program to sign up and be a mentee to someone who is definitely going to try to support my goals.

Clarence and I met under these incredibly unique circumstances, where if it weren’t for those series of events mentioned before that led to us meeting, The Wolves wouldn’t have been made, and we wouldn’t have known each other. I am eternally grateful to Clarence, firstly, but I also want to give a special shoutout to the Tabletop Mentorship Program that is hosted by the lovely Mike Belsole and Grace Kendall that led to us getting together.

All right, so after a few months in the mentorship program, I had almost nothing to show for it. I was obsessing over the game Glory to Rome and wanted to do a city rejuvination game with concepts inspired by it. I was off to a coldboywinter start as while I never knew I had it in me, I was approaching things slowly, in my head, without working nearly anything out.

Clarence started to provide some guidance: “show me”, not just “tell me” type of guidance. All sorts of real conversations were had to help push it out of me, but the biggest takeaway from all of this was that it’s okay to ask for help, and it’s a glorious thing to have a person, like Clarence, in your corner, believing in you, and attempting to hold you accountable. It was something similar to a penpal of sorts…getting to know someone cut from the same cloth, offering to be a sherpa or just a person to talk to, and we kept in touch over the weeks/months.

Oh, I remember the day. It was raining outside. I was wearing my favorite shirt and probably shorts, with my pasta water boiling over when I got a notification buzzing sensation in my pocket. Clarence asked what games I was working on and whether we could meet about a potential co-design. Grinning from ear to ear, that moment woke me right up. That was all I needed to hear. It was a pasta primapassion for those wondering what was made that evening.

I love working with others. I love building something and solving problems with others. This had the make-up of something great from the get go. We were in high spirits, and we needed a project to really motivate us, and most of all, keep us connected. We started considering different game concepts and mechanisms to work on with seemingly endless lists of random themes. With a goal of publication in mind, we looked at current games and marketability, eventually settling on basing a game on our mutual interest in wolves.

The Hunt Is On

Ashwin: Underrepresentation is a big thing for me, and not just about me being a minority, but also designing around an under-served subject matter. Shining a bright, elevated spotlight on wolves was a key driver in my desire to theme a game around them. Wolves are hunted still to this day and often characterized as vicious, villainous creatures, when they are quite the opposite. They are nomadic, territorial, and a great indicator of a thriving ecosystem. I wanted to break these harmful stereotypes, educate players about our endangered wolves, and as much as possible, make the game’s mechanisms mimic what wolves are like in real life, from how they move as a pack, how they stay territorial, prowl and survey the land for what prey they typically hunt to how they make their homes near water sources.

We looked at types of wolves, and while there weren’t many outside of a few regional species, most sources of material were describing wolves in a wolf pack led by a pair of alpha wolves. This clicked instantly with us as we could use wolves in different ways and maybe not asymmetrically. In certain regions, pack sizes are large, upwards of 20-30, but a loose definition of a wolf pack described them peaking at no larger than 8-12 wolves. How convenient. Pinch me. We’re really doing this!

It came quickly to us. In mere hours after a 4:30am text from me saying, “Yo Clarence, you up?”, we were penciling in major thematic mechanisms from wanting wolves to grow and strengthen their pack, evolve in the types of actions players would do, and hunt in this game while fighting for control of what is considered theirs. It was inspiring. Out of thin air, we found something we could really sink our teeth into.

[twitter=1588565788557860864]

Clarence: After settling on a wolf theme, we decided on some core design pillars. We wanted a competitive game that involved minimal randomness. We wanted high player agency and high interactivity. We wanted to support 3-5 players minimum. We wanted games to run no longer than 90 minutes and ideally closer to 60. We wanted the game to be about authentic, natural wolves and not some cartoony or anthropomorphized version of wolves. We wanted strong connections between theme and mechanisms.

We kept these design pillars in a shared Google Sheet that served as a sort of living design document and reference throughout the project. Occasionally, when thinking about what direction to take the design, we’d go back to these pillars to confirm that what we did would still be in service to those pillars.

It was almost too easy to pick a title for our game. Originally, we simply called it “Wolf”. We were surprised that no existing games already used that title. Plus, it was one of those four-letter titles that seem so trendy these days.

Our original logo for “Wolf”

We also took some time to brainstorm all the words we could think of that might be associated with wolves. That word list would help guide what components, actions, and systems we built into the game. Mechanically, we quickly settled on grid movement and area control as key game mechanisms that made sense for controlling packs of wolves in a competitive game.

Ashwin and I also had a shared love of the game Hansa Teutonica. From the very first iteration of “Wolf”, we had a core system in which you could add pieces to the shared central board from your player board, and when you did so, you simultaneously revealed upgraded abilities on your player board. That system has existed in every iteration of the game and owes quite a bit to Hansa Teutonica.

Game Design Goes Digital

Clarence: One distinctive fact about “Wolf” is that it’s likely one of the first board games in which design, playtesting, iteration, and pitching was all done completely digitally and online. We never created a physical prototype or met with anyone in person. In fact, the first time we ever held a physical version of the game in our hands was when we finally received a production copy a few months ago. It was all because the pandemic changed everything.

When Covid began shutting down in-person events in early 2020 and for the foreseeable future, the tabletop game design community faced a moment of reckoning. Either designers could wait the pandemic out and put their designs on hold until some unknown day when things returned to normal, or they could pivot into unfamiliar digital spaces on Discord and Tabletop Simulator to continue creating in spite of the circumstances.

Many designers refused to take the leap to digital, but thankfully an online design community spearheaded by Gil Hova began to take shape and flourish. Although it was started by designers from New York, it quickly reached people across the nation and inspired many similar digital playtest groups that came after.

We built our first playable prototype of “Wolf” in June 2020 on Tabletop Simulator. It was the height of uncertainty with regards to the pandemic, but digital board game design was getting its legs and becoming more and more accepted. By this time, there were weekly online playtest meet-ups, online publisher speed-pitching events, and even weekend-long online playtest conventions like Protospiel Online.

First playable prototype (in Tabletop Simulator)

There were times during the height of the pandemic when I was unsure what would happen to board games in a world where people couldn’t gather, but the rapid industry adoption of digital alternatives gave me a lot of hope for our little hobby. I also became very hopeful about the fact that the shift to digital might actually help to democratize design in a way. Suddenly, even if you lived in a very remote part of the world with no local design community or had no money to travel to conventions, you could still design, playtest, and pitch to publishers. All you needed was a decent computer. Marginalized voices had a new way to access the industry.

As strange as it sounds, I’ve totally embraced the forced shift to digital in this distinctly non-digital industry. Yes, digital prototyping and playtesting have some quirks, but they also have some clear advantages over in-person work. Digital allows for extremely fast iteration when you don’t have to print and assemble new prototypes constantly. It allows you to network with and utilize an entire digital world of other designers and playtesters. And it makes for easy pitching and demoing with publishers without having to wait for in-person conventions. Even now that in-person events have returned, I am continuing many of my digital habits that I learned during the worst of the pandemic.

Ashwin: Digital skills were surfacing as a valuable resource, and a willingness to adapt to new, uncharted territories and vibrant communities felt like a necessary trait for which I was prepared. I have quite a unique set of skills that were able to be tapped into, and I crafted time into my schedule to be a resource for many, in addition to honing my skills to make this hobby a reality. I was attending various digital groups to learn from others how they would present, test, and work on their projects in order to implement these practices into my process. I was able to cram what could have been years of playtesting into just months, and from that, bolstered the confidence I never knew I had to exist in this space. Untethered by location, time of day, or group, I found myself in a mix of everywhere I wanted to be all at once.

How convenient! I had access to all sorts of like-minded people who want to exist in this space with me and help “Wolf” stand on its own! I will always preach: Playtest your game dozens of times, with dozens of different people. You won’t know until you do that your game is ready for next steps.

Our game took various forms, and you know what — those forms were all great! Learn from those versions, and let all those ideas fly, baby! From making maps that looked like literal wolves, to mimicking 18xx and Age of Steam maps for inspiration, we were able to quickly realize the type of game we could make, and iterate live, in the moment, testing and reviewing dozens of game board designs just because we could. We could actually get a glimpse of games we knew about, but had not played and were able to compare components and table presence with just a click of my mouse.

Decisions were made, easily, with the power of co-ordination digitally, and access to an endless shelf of resources ready for us to utilize. The game Silk had these very distinct-looking wooden meeples. Let’s just copy and paste them in! A game similar to Agricola had wooden donkey pieces — and they could easily be used to represent wolves! We’re just playing and prototyping with ideas here, finding inspiration along the way.

I also took this time to consider what the game could look like with modular set-ups. Revisit it a hundred times with different permutations, then see what lands and what could work in a physical setting. Digitally, things won’t slide or shuffle, but maybe to prevent an issue with a physical copy, perhaps we can design to have the pieces nest within each other, leaving no doubt. Using NURBS Software and the Adobe Creative Suite in conjunction with free vector and .svg sites like thenounproject, we were rolling. Now, if only we could figure out how players would meaningfully enact these wolves on the board!

Building Our Lair

Clarence: During those first design iterations, we already had most of the actions you could take on your turn. You could move, build a den, howl at lone wolves to recruit them into your pack, and mark territory by placing scent markers which also revealed upgrades on your player board. From researching different real-life varieties of wolves, we knew that we wanted the central board to be a hex grid composed of five different terrain types, each of which could support its own wolf type — but we didn’t yet know what impact terrain should have on the game. Everything was working fine, but the central board was meaningless.

As days passed looking for an answer, I found myself listening to a game-design podcast, and they briefly mentioned a prototype that utilized double-sided action cards. When you used an action, you flipped it over and revealed a different action you could take next time. I was fascinated by that idea and was quickly inspired to figure out how something like that could work in “Wolf”, hopefully in a way that made terrain meaningful.

I started by giving each player five double-sided terrain cards — much like the tiles in the published game — but they were only for movement. To move through grass hexes, then forest ones, you had to flip one grass and one forest card. I also wanted to be able to flip two matching terrains to move a nature spirit component we had at the time.

[twitter=1282521394396487680]

Soon after, the way movement worked was tweaked and the nature spirit was scrapped, but the idea of flipping terrain cards to move and flipping multiple matching terrain cards for more powerful actions remained — and it ultimately became the core of what I consider the most unique and interesting system in The Wolves.

Ashwin: You’re not wrong, Clarence! Okay, so wolves don’t literally pick up pieces of terrain and flip them, but a mechanical hook that leaned into a very popular typology in games, and a heuristic gamers of all kinds can understand — flip this, it becomes that — really helped expedite the feel we wanted in this game.

We quickly glanced at a game called St. Petersburg in which the cards file down and clog up when players are not interacting with them. Before we figured out that five terrain cards were what we wanted, we played around with a deck of cards, as well as cards that were played and arranged, but quickly we became deranged.

We wanted the actual execution of actions to be snappy, quick, and serviceable. Approaching each action may take a quick sweep of the game state, but each action was purposeful and, with the action system implemented, intentional.

So yes, as Clarence mentioned above, we landed on five double-sided terrain cards and quickly made these cards to match the types of terrain, delivering a system in which both sides of the tiles represented a unique sequence. The dark green wolves had grass turn into forest, and another card turning forest into ice, while the light blue wolves had ice turn into desert, and ice turn into grass. With these overlaps, each faction will inevitably be fighting for different types of terrain, but this felt off in one aspect: Shouldn’t the dark green wolves have an easier time in their dark green habitat? While we struggled initially with the fluidity of the mechanism, we were determined that we could find an answer that both improved player agency and added tension to the puzzle to make it feel rewarding. To the digital drawing board!

Awoooo

Clarence: Once we had the core action system figured out, it quickly became our and our playtesters’ favorite part of the game. The constant mini-puzzle on your player board was just the right amount of challenge to keep every turn interesting. The game was starting to sing.

We continued to test and iterate over the next few months. We added a faction-specific sixth terrain card to each player, giving the game just a hint of asymmetry. We added the powerful three-terrain dominate action that provided conflict, tension, and memorable moments. We switched from a static central board to modular tiles that could expand with player count. We introduced wild terrain tokens, bonus action tokens, and countless other minor tweaks.

[twitter=1285223134526943233]

[twitter=1289610259980382208]

However, we were still missing one crucial piece. We didn’t know how the game would end. We initially thought the game would end based on a player placing all their wolves or dens. What actually happened was that for the first ten or so playtests, we just called the game after an hour when it was clear we weren’t going to reach the end trigger within our desired playtime. The answer, it turns out, was moonlight.

From the first day of brainstorming we thought about having some sort of timer element related to moon phases. As we were searching for an endgame trigger, it seemed like a good time to revisit that notion, so we made a moonlight tracker board that looked a bit like a calendar and put moon phases on certain dates that would trigger scoring of certain regions on the board. Players would control the timing because every piece that came off the central board would move to the moonlight tracker, advancing it to the next date.

[twitter=1298625235021778945]

It was exactly what the game needed. It gave players agency and a reason to go to a region quickly. It created the sense of migration that is key to the finished product. Most importantly, though, our playtests now actually started to finish within our desired playtime!

Ashwin: This is the meat and potatoes of The Wolves story! You were fed a few appetizers, a glass of wine with notes of tree bark, but this is the main course. The SIXTH Terrain Card! People! This completely changed our game for the better. What was sticky started to feel smooth. Players were able to work with the puzzle, but not be hamstrung because of it. Players could create combinations now, prepare for future turns, and also uncover contingency plans, knowing that their cards won’t change, but the drama of what happens on the game board inevitably will!

Most area-majority games come with a feeling of withholding and passivity. What’s mine is mine, and if I show aggression, it often benefits the other players. With a pillar of design being engagement and interaction, starting players off in their corners of the world seemed a bit off-putting.

Early in development, we came up with an idea in which players start in the middle, in each other’s way from the jump. Listening to feedback and revisiting conversations of our own, we determined that the pair of alpha wolves needed to split off and not necessarily clump up. We wanted players on their toes, sure, but also as a means of flexibility to have options on which action to take when. We created a chasm or donut hole in the middle of the central tile and forced players to split up their alpha wolves. Thematically, this works as often one is hunting, while the other is training or nursing the pack. While grouping up could still inevitably happen, this was now a choice we are giving the players to add to their strategy.

Beyond the elegance and beauty that the game presents in its appearance, which was beyond our wildest dreams by the way, we wanted the game to feel elegant — elegant in that nothing was out of reach or inaccessible and that everything happened to have a purpose. No long-term artificial aspects were talked about as wanting to find its way into the game.

The region tiles, as mentioned before, took on many forms. The patterning math behind it all was set to five players, with every combination appearing twice, but no region tile had the same exact patterning. Intentionally, the free action of hunting prey happens around multiple terrain types, which means it takes more actions to surround the prey. Keeping prey token accrual as unique and not repetitive meant that all wolves had to keep moving, allowing for planning and preparing for future turns while also staying present in your current state of affairs.

We tuned the game to create more story and arc. We added and affixed extra action tokens to hunting prey to give permission to players to go crazy and have everlasting memories and moments in games that often miss the intention of why games exist. Similarly, as mimicry often leads to stagnation, offering another path towards extra exciting and potentially threatening future actions through the use of wild terrain tokens gave players the chance to compete and get out of any possible tricky spot easier, potentially even ramping up the pace of the game.

Lairs being required to be next to water features was a way of guarding players against themselves because if lairs could be built on edges of the map, it could lead to stale game states. By going into each region tile, it enriched the meaning and intentionality to do these actions over others. I could keep going with all the subtleties, but through each iteration and revision, things felt cleaner, refined, and cared for, which reflected how players were feeling.

Finding Our Pack

Clarence: We were now getting consistent positive feedback on the game. Playtesters unfailingly mentioned our action system as the most unique and interesting thing about the game, but maybe more importantly, we finally knew how the game would end. That was the last missing piece before starting the pitch process and looking for potential publishers.

We looked for publishers that had done medium-weight games, had done an animal theme, had done area control and/or grid movement, and had a good track record with their production values. There actually weren’t a huge number of publishers that fit all these criteria. We ended up picking out about a dozen publishers and, starting in October 2020, sent out pitch e-mails with a sell sheet and overview video.

Our checklist to prep for pitching

About one-third of the publishers never replied at all. Another one-third said “no”. Some had full production pipelines. Some didn’t want to publish a wolf theme, but also realized that changing the theme would likely do it a disservice. Some said the idea didn’t excite them or didn’t fit their plans. But the last one-third were curious about the game and wanted to spend some time evaluating it.

Around this same time, there were a few programs emerging that were trying to help designers get matched up with publishers in this new digital world brought on by the pandemic. We entered “Wolf” into the Board Date Project and The Pitch Project. “Wolf” was selected for the Board Date Project, but we received no contacts from publishers. “Wolf” wasn’t selected at all for The Pitch Project. This was pretty disappointing, but we still had a lot of faith in the game.

About a month later, Heather O’Neill of 9th Level Games ran another one of her great Publisher Speed Pitching events. It was at this event that we got to pitch “Wolf” to Alex Cutler at Pandasaurus Games. After demoing the game, Alex was immediately enamored with the terrain-flipping action system and felt like “Wolf” could fit well in their line-up and be developed into a published product with minimal mechanical changes. After a demo with the owners, we were given an offer to sign the game! We also received a comparable offer from a second publisher, but Pandasaurus was a bit higher on our list, so we decided to become part of the Pandasaurus family.

A Wolf in Pandasaurus Clothing

Clarence: After signing, Alex took the lead on development of the game. He liked most of what we had designed and didn’t want to make any broad, sweeping changes. It would be more like tweaking rules and massaging numbers.

For most of our design process, we had felt that the interaction between players was key to the fun of the game, and that you needed at least three to get that interaction, so we pitched “Wolf” as a 3-5 player game. However, there was a strong preference from Pandasaurus for adding two-player support, if possible.

Luckily, one of the very last things we did before signing the game was trying it once at two players with no rules changes, just to see what would happen. To our surprise, it didn’t completely break or fall apart. It was still an enjoyable game, but it did have some quirks. Alex ironed those quirks out with some special rules for a two-player variant, including tweaked score values and a neutral wolf pack.

Alex also added bonus tokens and VP to the attribute tracks. He also simplified the distribution of prey tokens. Originally, we had a rule that two opposing pieces could never occupy the same hex. Alex introduced the concept of pushing and the piece hierarchy to allow for more interaction.

An early 3D rendering to explore what the board and pieces could look like

There were also a few non-mechanical changes that needed to be made. The double-sided terrain cards would become thick punchboard tiles. That would make them much easier to handle once they finally existed in the physical world.

Scent markers would also need to be changed because dominating a scent marker by howling doesn’t quite make sense. Also, there was never a good plan for what a scent marker would actually look like as a wooden piece. The team eventually settled on changing scent markers into small dens and dens into large lairs. This change meant the end of all the pee jokes that inevitably happened during the prototype versions of the game.

Of course, I can’t talk about the production process without mentioning Pauliina Linjama. Pandasaurus brought her on to do the art, and we could not be more thrilled with the work she created. It really takes the game to another level. The wolf eye box cover is jaw-dropping and is consistently one of the first things to draw people in.

[twitter=1555550657926627329]

[twitter=1578318291604369408]

[twitter=1581254725202165761]

With a sold-out debut at SPIEL ’22 and a brief trip to the top of the BGG Hotness charts, it’s been quite the whirlwind journey for us and The Wolves. We are both very proud of the finished product, and we’re excited to see it soon on your gaming tables!

U svijetu društvenih igara, Earth se ističe kao igra koja kombinira ekološku svjesnost, strategiju i prekrasnu umjetnost. Ako ste ljubitelj

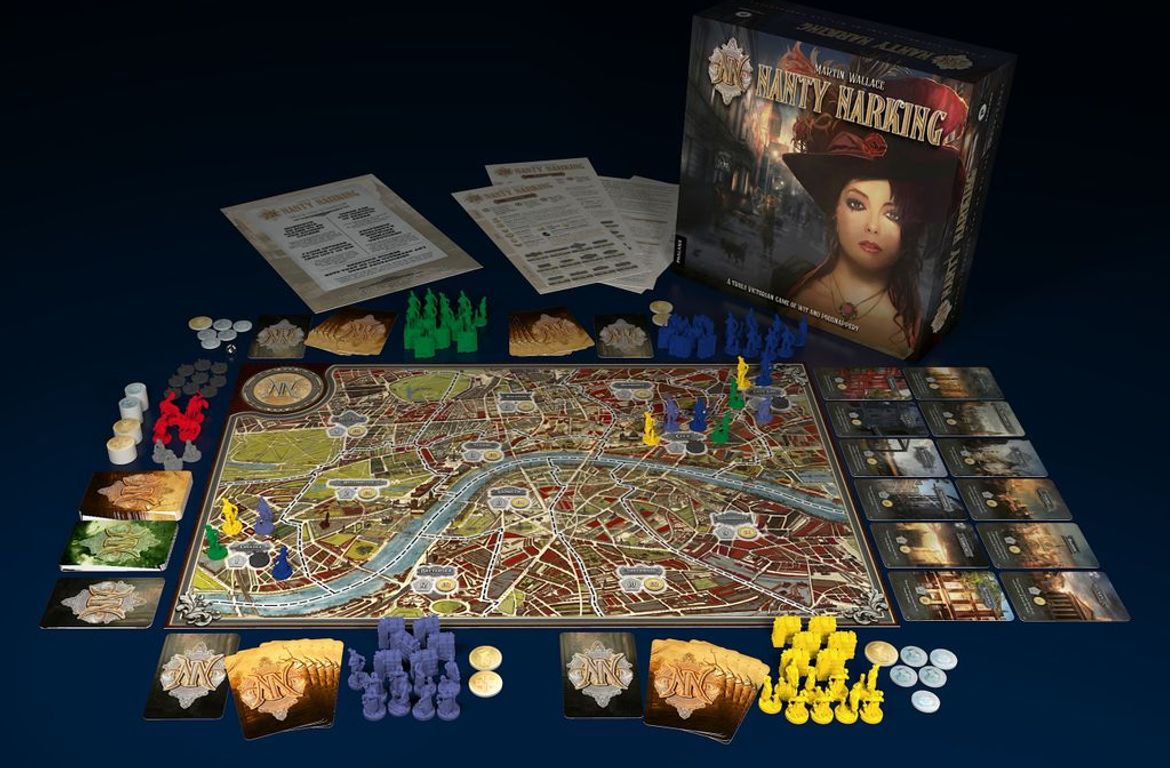

U svijetu društvenih igara, rijetko koja igra uspijeva obuhvatiti bogatstvo povijesti, strategije i priče poput Nanty Narkinga. Ova igra, smještena